Copyright 1996 Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Reprinted, with permission, from IEEE, ENGINEERING IN MEDICINE AND BIOLOGY Magazine, Volume 15, Number 3, May/June 1996.

This material is posted here with permission of the IEEE. Such permission of the IEEE does not in any way imply IEEE endorsement of any of Tsuei's products or services. Internal or personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution must be obtained from the IEEE by sending a blank email message to [email protected].

By choosing to view this document, you agree to all provisions of the copyright laws protecting it.

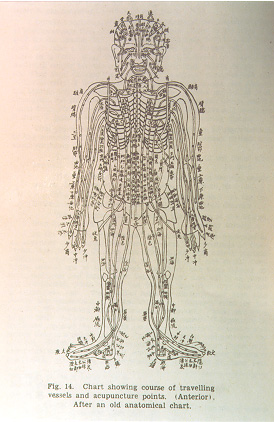

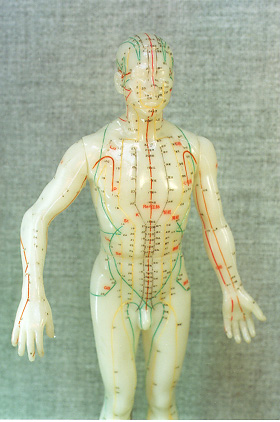

Acupuncture is a therapeutic modality used in China as early as the late stone age. Throughout Chinese history both acupuncture theory and practice has steadily evolved into an increasingly rich and complex system, eventually offering treatments for virtually every form of medical condition. Much of the history of the development of acupuncture therapeutics can be seen in the evolution of the needles themselves, but the meridian system is of primary importance, and the conceptualization of the system has changed very little in the last 2000 years (Figs. 1 and 2).

Acupuncture has long been considered more important then herbal pharmacology. The earliest classical books on traditional Chinese medicine discuss Acupuncture and do not discuss herbal pharmacology. These include Huangdi's Internal Classic (ca. 100 B.C.E.) and two other works that pre-date it, the Moxibustion Classic with Eleven Foot-Hand Channels and the Moxibustion Classic with Eleven Ying-yang Channels, both of which were discovered during the Mawangdui tomb excavations in 1973. [1] There is even a traditional saying: "first you use the needle (acupuncture), then fire (moxibustion), and then herbs."

Figure 1: A traditional diagram of the meridians along on the front of the body

Acupuncture did not enter modern Western consciousness until the 1970's when China ended a period of isolation and resumed foreign political and cultural contacts. In 1972 the respected New York Times columnist James Reston underwent an emergency appendectomy while in China. He latter wrote about acupuncture treatment for post-operative pain that was very successful. This report attracted attention and many American physicians and researchers went to China to observe and learn acupuncture techniques.

It appeared as though Acupuncture was used to treat everything in China, but the number of accepted acupuncture applications has grown very slowly in the West. The first area of partial acceptance was in analgesia, which is still the area where its effectiveness is best documented [2]. Acupuncture research has since become a very broad, active area both in Asia and the West. Research at the Shanghai Institute has demonstrated acupuncture's effect on various biological systems, including the digestive tract, cardiovascular system (helpful in hypotensive states), immune system (phagocytosis), and the endocrine system (the secretion of ACTH, oxytocin, vasopressin, norepinephrine, follicle stimulating hormone, prolactin, and 17-hydroxycorticosteroids) [3]. A recent issue of the bilingual, Chinese journal Acupuncture Research includes successful studies of acupuncture treatment for hemiparalysis, facial paralysis, cervical spondylosis, humeral epicondylitis, herpes zoster, and lumbago [4].Current research in North American and Europe includes uterine contractions [5], pulmonary disease [6], addiction, mental disorders, and as an adjunct to AIDS treatment [7]. Research continues, but widespread acceptance and integration are still far from realized.

Figure 2: A modern "acupuncture doll"

The primary reason for the slow acceptance of acupuncture is the lingering suspicion that there is no substantial, scientific reality behind it because a demonstrable mechanism of action has yet to be found. For the most part, early attempts to "explain" acupuncture have been either thinly disguised denials or have embraced and verified acupuncture only partially, disproving traditional acupuncture as much as validating it. The most prevalent example of the former is the argument that any effect acupuncture may have is psychogenetic, a placebo effect. This has been disproven by successful studies of acupuncture in animals, many examples of which can be found in Kuo and Kuo. [2] Two important forms of partial validation of acupuncture are the neuralphysiological and neurohormonal schools. The neuralphysiological school defines acupuncture points on "roughly dermatome basis; partially involv[ing] 'long' reflexes to distant parts of the body, which implicates a distribution by specific spinal segments or nerves; and are partially via unknown connections." [8] This could explain remote stimulation, but as the quote suggests, it is a very incomplete explanation. Neurohormonal theories center on the release of neurohormones triggered by the pain and microphysical damage caused by needle insertion. This has been used primarily to explain acupuncture-induced general analgesics, but it can explain little else.

Both of the above explanations are attempts to use structures and concepts acceptable to the mainstream medical community to explain acupuncture. But in grafting acupuncture to Western medical theory, aspects foreign to orthodox medicine are simply jettisoned. Because of the emphasis on genetics, anatomy, physiology, and bio-chemistry in modern medicine, and a near complete denial of energetic processes in the body, chi (body energy) and meridians (paths of body energy flow) are either ignored or considered fallacies with some metaphorical or pneumonic value. Emphasis is placed by most researchers on the needle and the physical effect of its insertion into the skin, but this side of acupuncture is not essential. According to our research, acupuncture is essentially manipulation of bodily energy as it flows through the meridian system. The acupuncture needle is only one of many possible tools used to accomplish this. In the remainder of this article, "meridian theory" will be understood to include acupuncture theory and practice. "Meridian" is used to stand for both the meridian itself and the acupuncture points along the meridian.

A bio-physical or bio-chemical approach to acupuncture robs it of its actual foundation, and because of this acupuncture research to date has been only partially successful. Fortunately, advances in physics, electro-magnetism, quantum-mechanics, and bio-energetic research have enabled researchers to develop a paradigm that for the first time successfully explains the majority of acupuncture related phenomena. [9] We have embraced this bio-energetic paradigm not simply because it can explain more of acupuncture phenomena, but because it is a true description of acupuncture's mechanism of action and is an important facet of all life processes. The only way to address acupuncture successfully and scientifically is through the meridian system.

This four-article series will attempt to give a fairly complete representation of meridian theory research based on the bio-energetic paradigm. This, the first article, covers traditional acupuncture, early research into the electrical properties of acupuncture points, and basic EDS Test (EDST) methodologies. The theoretical foundation for the bio-energetic paradigm is discussed in two articles by Physicist Kuo Gen CHEN. The fourth article is a review of research into an application of bio-energetic properties called the electrodermal screening system (EDSS). In that article Dr. F.M.K. Lam, Prof. Pesus Chou, and I hope to demonstrate the effectiveness of the EDSS as a screening/diagnostic method and offer evidence of the causal connection between acupuncture points, meridians, and internal organs.

Traditional Meridian Theory

According to traditional Chinese medicine, a form of bodily energy called chi is generated in internal organs and systems. This energy combines with breath and circulates throughout the body, forming paths called meridians. The meridians form a complex, multilevel network which connects the various areas of the body, including the surfaces with the internal. All of the various meridian systems work together to assure the flow and distributon of chi thoughout the body, thus controlling all bodily functions. The interwoven meridian systems and the possibilities for diagnosis and treatment they offer, are called meridian theory. When an organ or system is not balanced, related acupuncture points may become tender or red, allowing for diagnosis. For treatment, a point on the skin is stimulated through pressure, suction, heat, or needle insertion, affecting the circulation of chi, which in turn affects related internal organs and systems.

"Meridian" is the most common translation of the Chinese ching-lo (jingluo), but it is a very imperfect translation. Ching means to pass through, and lo means a net or to connect. "Meridian" was originally used by French researchers to describe all meridians, and is used in this article in that sence. The term "channel" is used increasingly for all meridians, while some prefer to maintain the original distinction between ching and lo and use the terms channels and collaterals respectively. For them, meridian theory would be reffered to as the theory of channels and collaterals. There is another sub-classification of meridians called vessels. Although it is a valid distinction, it is not important to the immediate discussion.

Meridians are classified into 6 groups according to their location and function. The best known of the meridians are the 12 regular meridians, also called the major trunks. They connect with the organ they are named for by way of collateral meridians (see bellow) and run along the surface of the body either on the chest or back and along either both of the arms or both of the legs. These are the primary conduits for the passage of chi through the body, which flows through this network in a regular, 24-hour pattern. The 12 regular meridians therefore control or take part in every facet of the daily metabolic and physiological functioning of the body.

There are three meridian groupings directly associated with the regular meridians, each with 12 meridians. 1) Each of the divergent meridians arises from one of the 12 regular meridians, passes through the thorax or abdomen to join with the named organ, and then surface at the neck or head. 2) The muscle network meridians distribute chi from the 12 regular meridians among muscles, tendons, and joints, ensuring normal body motion and flexibility. This circulation of chi is referred to as superficial because there is no direct connection with an internal organ. 3) The cutaneous network meridians run parallel to the regular meridians in the cutaneous skin layer and are therefore considered even more superficial. We believe that they are a part of the function of the sensory nervous system.

The 8 extra meridians (also referred to as vessels) are the paths by which the 12 regular meridians connect, share chi, and support each other. None of the individual extra meridians are associated with a specific organ or regular meridian, though all of them connect with a number of other meridians. Their paths are considered superficial but deep. It is through the extra meridians that imbalances in chi are regulated through storage and drainage. The most important of the extra meridians are the govorner meridian, which runs along the middle of the back, and the conception meridian, which runs along the middle of the chest and stomach.

The system of 15 collateral meridians is responsible for the thorough and complete circulation of chi. One collateral meridian arises from each of the 12 regular meridians, the governor and conception meridians, and from the spleen (which does not have a regular meridian). Each of the collateral meridians branch out, forming minute or "grandson" collateral meridians, creating both horizontal and vertical connections within the complete meridian system.